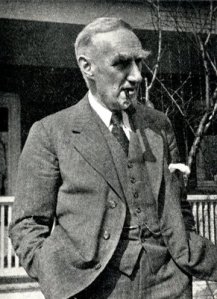

John Boyd Orr from the http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk

Born in Ayrshire he trained as a doctor at Glasgow University where he won a gold medal for his thesis. In 1913 he was appointed to oversee the development of a new research institute at Aberdeen University. This project was interrupted by the First World War during which he served in the Army as a doctor and was at the battles of the Somme and Passchendaele. Returning to Aberdeen in 1919 he used his considerable financial and persuasive skills to develop the Rowett Institute which was carrying out research into animal nutrition.

He was asked by the British government to investigate the idea of a national food policy and the resulting report, Food, Health and Income, was published in 1937. It made uneasy reading for those in government. It mustered considerable research to demonstrate that many people in Britain were simply too poor to eat a nourishing diet. The report stated,

“… a diet completed adequate for health according to modern standards is reached only at an income level above that of 50% of the population.” John Boyd Orr, Food, Health and Income, MacMillian, p.44

During World War Two he advised Lord Woolton and helped shape the wartime diet for the better. In 1945 he retired as the Director of the Rowett Institute and began a new international career becoming as the first Director General of the Food and Agricultural Organisation. He proposed a World Food Board to distribute food to where it was needed. It was an ambitious plan and when it failed Orr resigned in disappointment. It may have been a Utopian plan but you have to love him for trying.